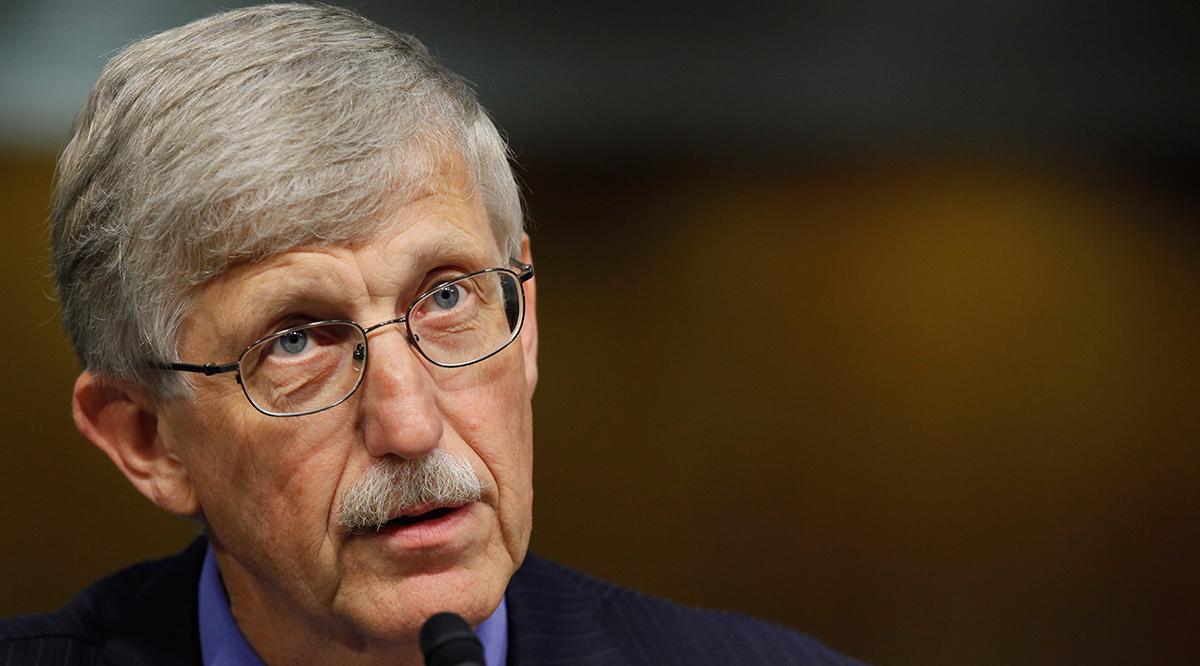

Francis Collins, MD, PhD, was being muzzled at the agency he once led.

The longtime director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) says he stepped down from his laboratory position there in February in the face of severe cutbacks to scientific research and restrictions on his ability to speak about that research.

“It just didn’t feel as if I was in a place that was able to contribute very much,” Collins recently said in an interview with AAMCNews.

So far this year, the administration has terminated 2,282 research grants totaling about $3.8 billion, including almost $2 billion in cuts to U.S. medical schools and hospitals, according to a June 2025 AAMC report. Another new AAMC report notes that the administration has proposed a fiscal year 2026 budget that would reduce NIH funding by $18 billion and has discussed eliminating funds for several of the agency's 27 institutes and centers and consolidating others.

A physician-geneticist, Collins was appointed director of the NIH by President Barack Obama in 2009, after having led the international project that mapped the human genetic code. He was asked to stay on by Presidents Trump and Biden, remaining at the helm through most of 2021, making him the longest-serving presidentially appointed NIH director. He served as acting science advisor to the president in 2022, then stayed on as a distinguished investigator in the intramural program of the NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute, doing research on type 2 diabetes and a rare form of premature aging called progeria.

Collins retired in February 2025, issuing a statement that praised NIH-funded research and its staff as “individuals of extraordinary intellect and integrity, selfless and hard-working.” In a subsequent interview with “60 Minutes,” Collins called the environment at the NIH this year “untenable,” citing limits on scientific communication, firing of staff, and halts to new projects enforced by political directives.

In an interview with AAMCNews, Collins shared what was happening inside the NIH before his departure, as well as the impact that cuts to NIH funding are having on the scientific enterprise and the future biomedical research workforce.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Why did you leave the NIH?

After January 20, my ability to get research done was increasingly compromised by limitations on being able to order supplies, by a prohibition against starting any new projects, and by a prohibition against speaking publicly about much of anything without approval from an administration appointee. And it wasn’t clear who that would be. It just didn’t feel as if I was in a place that was able to contribute very much, so I made the decision to retire.

Could you have stayed and had a voice to influence policy?

That’s a nice idea. But the constraints were such that I was prohibited from having a voice. I didn’t feel I could raise alarms about the harms that were being done to medical research. I was prohibited from speaking about it. I felt that if I was going to make any contribution, I’d have to be in a more public space. I have a voice now, but it’s outside of NIH.

A lot of what NIH funds is basic science, which focuses on discoveries that might or might not result in practical applications. How can you describe the value of basic science to the public? To most people, it seems nebulous. It might take 30 years of research to pay off in a practical way.

Yes, it’s hard for people to understand the importance of basic science. I think the best way to deal with that is to talk about examples.

I’ll reflect on my experience with cystic fibrosis research. The effort to try to do something for that almost-uniformly fatal disease started as a basic science enterprise to try to discover the nature of the gene that is misspelled. That was a hard slog back in the 1980s. Nobody would have supported [research into it] except NIH.

That work by my University of Michigan lab, working with Lap-Chee Tsui at the Hospital for Sick Kids in Toronto, led to the discovery of the gene [and the mutation that causes the disease] in 1989. Then, a partnership of NIH-funded research, philanthropy from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and investments by biotech and pharma led to a therapeutic breakthrough.

Now, 30 years after the gene discovery, young people with cystic fibrosis are planning for retirement instead of an early funeral.

Or take the recent case of Baby KJ, who was born with severe CPS1 deficiency, [a genetic disorder that kills most affected babies in their first year]. Baby KJ was treated with a customized gene-editing therapy that was developed just six months after his birth. That would never have been possible without 20 or 30 years of deep investments to develop an approach that had the potential to fix a genetic misspelling in this disorder. It arose from basic science investigation of obscure viruses that infect bacteria, which is what led to the discovery of CRISPR. A lot of people would have said, “Why are you doing that?” Here you are.

When you go to your medicine cabinet and take out a bottle of pills [for any ailment you have], almost none of those medicines would be there if we didn’t have NIH supporting the basic science and then the [pharmaceutical] industry picking it up and turning it into a product. The whole thing falls apart if you don’t have the foundational [research], which is provided by NIH.

Is there a way to resolve the dilemma of people not knowing that their life-altering drugs were developed through basic science research funded by NIH?

The scientific community has not done a good job of getting compelling information in front of people to explain how this all works. That public inspiration probably isn’t going to happen by me or other scientists giving a lecture. To reach the average non-scientist, I believe we need to share stories from real people whose lives have been affected. Stories from someone who has been cured of sickle cell disease. Or someone with stage IV cancer, whose clinical trial just got terminated because of the steps taken by the administration in the last few months and who has now lost any real hope that there might be an answer for them.

Or a mom who has a child with a rare genetic disease and who talks about the hope she had about a trial before the funds were cut. It’s hard to hear stories like this and not feel empathy. We haven’t got that message out as effectively as we need to.

For the average person who doesn’t know much about NIH, is there a legitimate way to reexamine NIH funding and its mission?

I was NIH director for 12 years, under three presidents. We were reexamining the funding plan and the mission continuously. One of my first actions was to dissolve an NIH unit that I thought was not functioning in the way that it needed to. A new enterprise was created: the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, to make sure significant basic science discoveries didn’t get stuck without being moved forward into clinical applications.

Scientifically based reform efforts like that have always been a priority. But they’ve been done with careful consideration of the consequences. That’s not what’s happening now. The recent flood of cuts of budgets, staff, and projects is more like a slash-and-burn approach, without any apparent consideration of what these actions might mean for the future of America’s health.

There’s always room for improvement in any large organization like NIH. But that needs to be done in a fashion that reflects real vision, real scientific expertise, real consideration of downstream consequences, not in such a rapid and indiscriminate way.

What’s happening right now is careless. It’s heartless. It doesn’t consider the consequences for patients or for the people doing the work. And it is deeply demoralizing to the scientific workforce, in a way that is going to have lingering consequences for a very long time.

Let’s talk about that. There have been conversations about a brain drain, about scientists leaving NIH or even the United States. Do you see evidence of a brain drain?

I spend a lot of time talking to the younger component of our workforce, graduate students and postdocs. Roughly a third of those I’m speaking to are looking at plans to leave the country. They don’t see that they have a future here anymore. So, they’re looking at the U.K., they’re looking at Europe, they’re looking at Australia, all of which are putting out the red carpet to invite this talent to come to their countries. This is a drastic change. We used to be the number one place that talent wanted to be part of.

I can’t confidently tell those young scientists that this is going to get better in the near future. Congress has done little to stand up for what traditionally has been a very strong bipartisan agreement: that medical research is one of the wonderful things the government does. The NIH has been called the “crown jewel” of the federal government for decades. Now it seems that jewel has been knocked into the dust.

My deepest concern is that America is going to lose a whole generation of scientists. It will be very hard to recover from that.

The administration is talking about establishing a gold standard for medical science research. What is your response to that?

We’re all in favor of a gold standard for science. But it’s misleading, and even a little insulting, to say that somehow NIH didn’t already support that. Everything that NIH stands for is rigor in science. Yes, science makes mistakes, but the scientific process is self-correcting. There’s some implication here that NIH has been systematically sloppy. I reject that conclusion.

The rhetoric being put forward about gold standard science seems more like politics than science. And you know what happens when you mix science and politics. You just get politics.