While earning his doctorate at Harvard University, Semir Beyaz, PhD, focused his research on understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms that make cells behave the way they do. His work led him on a deep dive into immune cell dysfunction, particularly in the form of cancer.

“I studied why cells become selfish — that is, why they stop listening to the cues of the body and take over the whole system,” Beyaz explains.

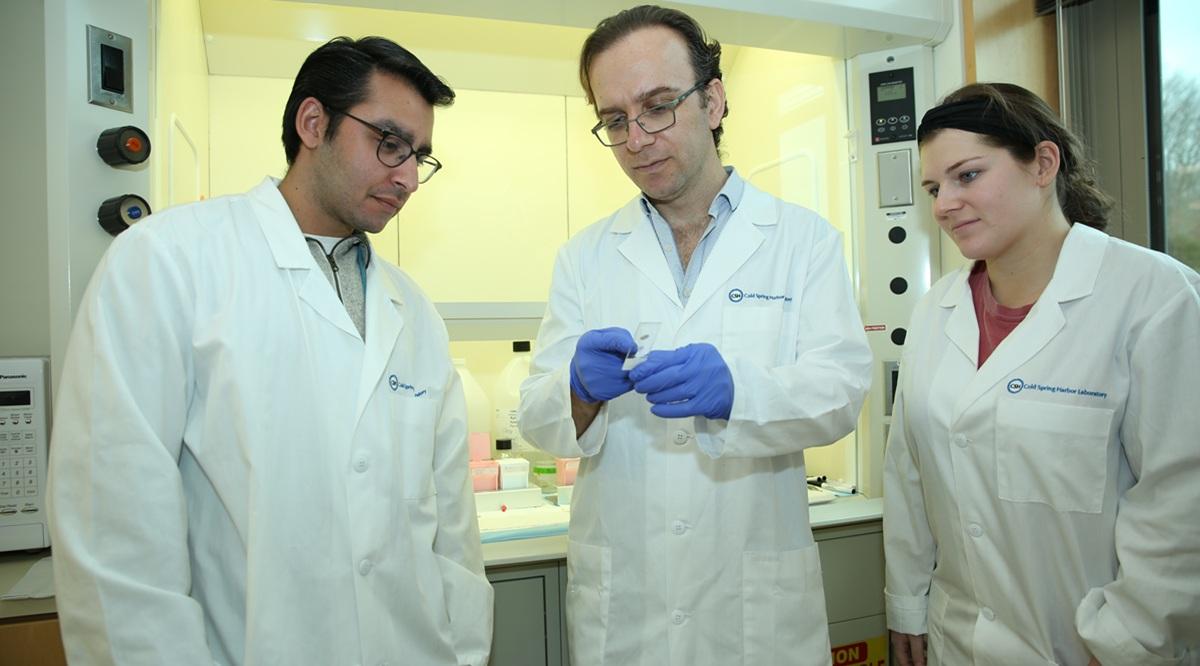

So eight years ago, when he set out to start his own lab at the Long Island, New York-based Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), a private, nonprofit biomedical research center, he wanted to home in on topics that were not cancer, but had similar characteristics and received less attention. He landed on endometriosis, a chronic condition in which the endometrial tissue that usually lines the uterus grows elsewhere in the body.

In endometriosis, the tissue “is spreading like a cancer,” Beyaz says. “It disrupts the way the body works. It’s a chronic inflammatory disease with a significant impact on the well-being of patients suffering from it. It increases all-cause mortality. It’s a very serious condition. We need to provide an answer to hundreds of millions of people.”

Endometriosis affects an estimated 1 in 10 women of reproductive age worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, and patients in the United States can wait five to seven years from symptom onset to receive a diagnosis, in part because the only current way to confirm the diagnosis is through a minimally invasive surgery and biopsy.

However, as public awareness of the condition and interest in creating better diagnostic tools and treatment options has grown — building on decades of work by researchers, clinicians, and advocates — a flurry of research is advancing the field toward what researchers hope is real progress.

Within the past year, new research has demonstrated a correlation between endometriosis and a variety of chronic diseases, including cancer and autoimmune disorders. Also, researchers and biomedical companies are developing diagnostic tests, including a proof-of-concept at-home test created by a professor of nanomedicine at Pennsylvania State University. The test uses menstrual blood and is similar to a home pregnancy test. Another new, noninvasive option uses artificial intelligence (AI) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“I’ve [been] very encouraged by the number of people who are advocating and are in positions to actually influence research direction,” says Linda G. Griffith, PhD, a professor of biological and mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) who codirects the MIT Center for Gynepathology Research and has studied endometriosis for more than 15 years. “There’s been a sea change.”

Investing in women’s health

For most of history, the medical establishment has considered women’s bodies to be atypical. In the United States, women were rarely included in clinical trials until 1993, and investment in health issues that exclusively or disproportionately affect women has lagged. As of 2020, 5% of research and development funding globally went toward studying women’s health.

Endometriosis has been particularly neglected, in part because it is difficult to diagnose. Plus, many physicians assume it to be benign unless the patient is trying to conceive. But as more women have spoken out about their experiences with endometriosis — which can cause severe pain, heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, a higher risk of ovarian cancer, and complications such as organ damage — public and scientific interest in understanding the disease has also increased.

“I think social media and all these online platforms have helped,” says Joseph Nassif, MD, a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “We see more awareness in this new generation of doctors and patients."

Nassif, a surgeon who specializes in minimally invasive endometriosis surgery, says he’s noticed an acceleration in advancement of research following the increase in awareness.

“It’s very different from before,” he says. “When I started in this field 18 years ago, there were few [endometriosis] specialists and fewer patients [were] diagnosed.”

In August, the Gates Foundation announced a commitment to invest $2.5 billion in women’s health research globally by 2030. Endometriosis is one of its main target areas.

And with $20 million from private philanthropy, in April, CSHL opened the Seckin Endometriosis Research Center for Women’s Health, named for Tamer Seckin, MD, a renowned endometriosis surgeon and clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell. Beyaz will lead the center’s research into understanding the mechanisms behind endometriosis, with an eye toward developing therapies.

Beyaz has been collaborating with several scientists, clinicians, and engineers. This includes working with Griffith to study endometriosis in patient avatars, which are models made of polymer frames housing living cells that Griffith developed. These models allow scientists to study organs with more accuracy than in mice, which don’t naturally menstruate.

At MIT, Griffith is also leading a “moon shot for menstruation science,” which, with private funding and support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is helping her team uncover more about the mechanisms behind menstruation and the disorders related to it.

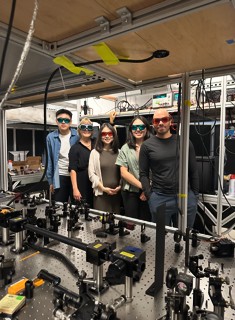

Linda Griffith, PhD, second from the left, poses with the MIT endometrium team in the Computational Biophotonics Lab.

“We’re inching our way to understanding how to diagnose patients in a way that points them to a therapy that’s going to work for them, so they don’t have to cycle through a bunch of therapies that don’t work for months and months,” says Griffith, who was diagnosed with endometriosis in 1988 after years of debilitating symptoms.

A step change in the field

Since she shared her personal and professional story with the New York Times in 2021, Griffith has fielded an increasing number of emails and calls from people interested in endometriosis — ranging from fellow patients and young scientists hoping to study the disease to leaders in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries asking her advice on investing in women’s health interventions.

Now more researchers in labs across the globe are working to understand this disorder. About every other year for the past 39 years, these scientists have gathered for the World Congress on Endometriosis. The most recent one took place in Sydney in May.

“That meeting was like a step change from the one [that was held] two years before,” Griffith says. “The quality of work is so high. There are so many young investigators around the world working on this.”

Beyaz admits that, in his early years as an academic researcher focused on immune disorders and cancer, he wasn’t fully aware of the seriousness of endometriosis.

“Women’s health efforts have often been neglected,” he says. “The efforts science and medicine have put forth so far have not been sufficient to make big differences.”

But he hopes that his “outsider” perspective as someone who spent the formative years of his career researching the immune system, stem cells, and cancer, and his commitment to bringing together interdisciplinary teams, will help begin to move the needle on advancing the field. Not only would this help the women who suffer with endometriosis, he says, but understanding how endometriosis spreads could help unlock information about other diseases, including cancer and autoimmune disease.

“Diversity of experience is an important element when you’re going to generate a breakthrough,” Beyaz says. “That’s a philosophical choice for me; I like to study life across boundaries.”

Taking pain seriously

While the acceleration of research into endometriosis may generate excitement in the field, for the 1 in 10 women with endometriosis (a figure that may be an underestimate), it can seem frustratingly far from reality. Currently, most patients are advised to treat symptoms by taking birth control (if tolerated and the patient isn’t trying to conceive) and to manage pain with over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Apart from the lack of diagnostic tools and therapies for women who have endometriosis, many patients say that they experienced doctors and health care providers dismissing their symptoms or failing to fully investigate their complaints.

Such was the case for Diana Falzone. She had suffered from heavy bleeding and pain since she was a teenager, but the only solution doctors offered her was to go on birth control. When she was 32, she experienced an acute onset of pain so intense that she thought her appendix had burst. The doctor she saw in the emergency department concluded she must have the flu. It wasn’t until she got an appointment with a gynecological specialist weeks later that she heard the term “endometriosis.”

In the nine years since her diagnosis, Falzone, who is a journalist for NewsNation and an ambassador for the Endometriosis Foundation of America, has had multiple surgeries to excise the tissue taking over her abdomen. After one operation, her surgeon told her that the endometrial tissue had compromised her ureters, the ducts connecting the kidneys to the bladder. Had it been left untreated, she could have gone into kidney failure.

“It dawned on me, I never knew how serious endometriosis could be,” she says.

Her plea to doctors, from trainees to veterans, is to take their patients’ complaints seriously.

“I’ve realized that appointments are short and time is allotted, but don’t wave [the disease] off because you can’t easily see it or treat it,” she says.

Nassif, who was among the first cohorts of physicians to do an endometriosis surgery fellowship nearly 20 years ago, says that awareness of endometriosis has increased among doctors over time, but there’s still more to be done to educate people. He encourages the medical students he teaches to continually read the latest research in the field, to assist on complex surgeries, and to keep pushing for better care for their patients.

“We are speaking more about endometriosis, and our students and residents are seeing endometriosis more,” he says. “I still say this now to my students: Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease. We still have a lot to do.”