“What does it mean to be a person?”

It was a philosophical question that cardiologist and best-selling author Sandeep Jauhar, MD, PhD, wrestled with as he watched his father’s mental decline due to Alzheimer’s disease.

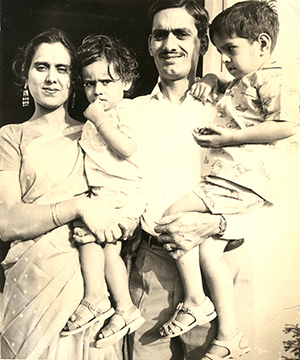

His father, Prem Jauhar, was an internationally recognized plant geneticist who grew up in poverty in India and used his skills to advance agriculture and relieve hunger.

“The experience of caregiving was the hardest journey I’ve ever taken,” Jauhar said at a session discussing his book, “My Father’s Brain: Understanding Life in the Shadow of Alzheimer’s,” at Learn Serve Lead 2023: The AAMC Annual Meeting on Saturday, Nov. 4. “It was hard to watch someone I so deeply respected, a titan in his field, become so mentally impaired.”

Is personhood conferred by a person’s cognitive abilities, their memories, or their economic productivity? Jauhar spoke candidly with session moderator Henry Bair, MD, a resident physician at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, about how deeply his firsthand experience as a caregiver to his father challenged his perception of what constitutes a meaningful life, a concept with which he still grapples.

“I think that in the Western world, we have a certain perspective that prioritizes intellect and reason and autonomy and rationality and forgets about the other things, the touchy-feely things that make us people,” Jauhar said.

Though Jauhar didn’t romanticize his caregiving experiences, acknowledging the frustration, family conflict, and loss of dignity that came with his father’s condition, he shared that witnessing his father find new enjoyment in simple things — his favorite ice cream, his son visiting him after work, the kindness of his hired caregiver — made him rethink his own perception of a meaningful life.

Jauhar’s experience also brought to light the shortcomings in the United States’ approach to elder and dementia care. While the government has invested heavily in research for Alzheimer’s treatment — with little progress until some recent breakthroughs — there has been far less investment in care for the millions of people currently living with the disease.

Jauhar discussed how, as a physician, it was important to him to understand the science and history behind Alzheimer’s. When he understood that the disease was attacking his father’s hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for emotional processing, he was more forgiving of his father’s outbursts.

But science can only go so far. Jauhar still experienced denial of his father’s condition and suffered the emotional ups and downs that come with caregiving.

When an audience member, a geriatrician who also was a caregiver to parents with Alzheimer’s disease, asked about the emotional toll on him despite his clinical knowledge, he recalled a memory from his father’s final days. He had been sitting with his father as he lay in bed when his father asked him to come lay down with him. Jauhar said he resisted at first, saying he needed to go home to have dinner with his family, but his father persisted. In those moments together, Jauhar’s father, who in his mental height rarely spoke of emotions, told his son he loved him and was proud of him.

The emotional experience grounded Jauhar in his father’s humanity.

“In the end, it's just about two humans interacting and everything else goes out the window.”

AAMCNews sat down with Jauhar several months ago to discuss what he learned about Alzheimer’s disease from his father and about the current challenges and progress in the field of treating and caring for people with the disease.

In your book, you write candidly about your family’s struggles and your own shortcomings in caring for your father during his illness. Were there any takeaways from your experience that you might have done differently?

There’s a lot that I would have done differently. I regret a lot of the frustration and anger I experienced — which is normal as a caregiver. Most caregivers who go through the journey obviously don’t emerge unscathed.

There is one specific thing I would have done earlier. I experienced an ethical dilemma about the fact that my siblings would routinely lie to my father to assuage his anxiety or stress. I found this extremely problematic but, in retrospect, I probably overthought it. For me, telling my father the truth was like telling him, “You’re still a part of my world and I still care about you. I still think that you’re a human being who's worth reckoning with.”

As a physician who’s been trained to level with his patients, to tell them the truth, and to not withhold bad news, I tried to apply this truth-telling paradigm to dementia caregiving, but it just didn’t work. I would share uncomfortable truths with my father. He would forget that my mother had died. My siblings would say things like, “Oh, mom’s on her way,” or “She’s on the airplane and she’s coming,” and I would tell him, “Dad, no, mom died. She died three years ago, and nothing we say is going to bring her back.” And that would cause him incredible anguish, which he would reexperience every few days when he would ask again, and I would level with him again. Unfortunately, it took a while, but I came to learn that there’s a different conception of dignity when it comes to being an Alzheimer’s caregiver. Telling someone the truth isn't the only way to uphold dignity. There’s also the idea to meet the person you’re caring for where they are in their reality and not forcing them to enter your reality or, let’s say, the general reality, whatever that means. My father’s reality was very different [from ours]. And so, eventually I came to learn that it’s ok to tell little white lies.

You also write about how much is still not known about Alzheimer’s disease. Where do you think we are now with research into therapies and prevention, or at least slowing down the degenerative process?

For a long time, Alzheimer’s was thought to be just the result of [amyloid] plaques and tangles in the brain, which are these abnormally folded proteins that clump together inside and outside neurons. That paradigm was called into question because anti-amyloid drugs didn’t seem to work. In fact, in some cases, they worsened cognitive impairment. So then the question arose, are plaques and tangles just a marker for some other process? For example, neuroinflammation? There were questions raised about whether viruses were the causative agent. Vascular abnormalities — fatty plaques building up in blood vessels — were also considered as a potential etiology because we know that cardiovascular risk factors tend to also be risk factors for Alzheimer’s. So there was a lot of questioning about what was the cause of the disease. It’s hard to come up with effective therapeutics unless we know the target that we need to focus on.

But, in recent years, because of the success of some new anti-amyloid drugs, it’s generally accepted that amyloid plaques do play a role in the disease. We now have at least two drugs, and the most recent data on donanemab, which is a monoclonal antibody that was just released, showed that the drug is probably as effective if not more effective than lecanemab, which is the Biogen drug, but does cause a little more brain bleeding. The side effect of brain bleeding is probably a direct result of the fact that it’s more efficacious at removing plaque. So there are risks to these new drugs, but it’s a hopeful time. We now know that there are drugs that slow the progression of the disease. We have never had those before. And the hope is that more effective drugs will be developed and that early diagnosis will make sense. For the longest time, doctors discouraged patients from getting PET scans to look for amyloid in the brain because there wasn’t really anything we could do about it. Now there is, so I’m guardedly optimistic about the outlook for Alzheimer’s therapies in the next decade.

In addition to the physiological factors, what role do psychosocial factors play in how a person with Alzheimer’s fares?

The fact is that the presence of amyloid plaques in the brain doesn’t correlate as strongly with the severity of disease as we would expect. There are other factors that come into play. There’s cognitive reserve: how many brain cells you start with or how many synaptic connections you have. But there’s also this idea of psychosocial reserve: having social connections that we know are protective. For example, we know that loneliness is a major factor in the incidence and progression of Alzheimer’s disease; people with plaques and tangles who are lonely have much greater risk and a faster progression to cognitive decline.

And the fact is that a lot of people with Alzheimer’s are lonely because society tends to shun patients who cannot participate in normal interactions. So, what can we do about it? That’s, hopefully, where my book comes in. To remind caregivers about what to expect so that they can be more patient and caring with their family members. That’s important in mitigating the horror of the disease, but it has physiological benefits as well.

Are there ways that you think the U.S. health care system could better care for people with dementia who may not be able to rely on family to care for them at home?

My experience abroad reminded me of the problems with Alzheimer’s care in this country. In the Netherlands, they’re building “dementia villages,” where folks with dementia can walk around and wander freely. In America, when they’re institutionalized, people with dementia tend to get locked up in memory units. The idea is that keeping them from wandering will prevent falls and bodily harm. I understand and empathize with that rationale. The problem is that you’re not really treating people humanely by locking them up.

With elder care in general, not just Alzheimer’s care, there’s this tension between autonomy and safety and, in America, we have decided to face that problem by focusing on safety. In the dementia village I visited in Amsterdam, they say, “Look, we don’t want people hurting themselves, but we’re willing to accept a certain level of risk to reap the benefits of allowing people to have agency to walk more freely.”

In America, the government doesn’t provide much help and there isn’t a cultural predisposition toward treating people who are declining humanely. So, what ends up happening is people tend to go into institutional settings which are lacking in humanity in many ways. I think change is happening though. There are dementia villages now being considered in San Diego; there’s one that's going to be built in Atlanta; and there’s a sort of dementia village in Ohio, so a new approach is coming. And one thing I found was really striking is that the costs of a dementia village in the Netherlands is the same as what a typical nursing home would cost — so they use the same amount of money, they just spend it differently. It was very encouraging to me that we can treat Alzheimer’s patients with dignity and humanity without breaking the bank.

As a physician speaking to other physicians, what would you want the take-away message about Alzheimer’s disease to be?

We’re at the threshold of a new era in Alzheimer’s care. There’s this sense that Alzheimer’s is just a horror show. It’s a chronic disease that kills so many Americans per year, and there’s nothing that can be done about it. Also, it’s different than physical illness in that it affects a person’s personhood, their autobiographical history, and their ability to relate to people, and so often results in institutional care. That was the prevailing view of Alzheimer’s. There's still some truth to this. But with the advent of new drugs as well as increased attention being paid to dementia, we are entering a new era. And so there’s a lot to be hopeful for.

The science — including drug development and research — that’s very important, but we also need to focus on caregiving. Resources, for the longest time, were just focused on the former at the expense of the latter. A lot of money was put into developing drugs, and I’d say probably 200 drugs were studied, and 200 out of 200 failed. There was this tremendous sense of pessimism in the field. At the same time, not much money was put into improving caregiving strategies and improving institutional settings. Now, I see there’s a lot of movement happening in both spheres, as new drugs are becoming available, and people understand that nursing homes for dementia patients need to be humanized.

It’s a hopeful time and I’m guardedly optimistic about what lies ahead.