Editor's note: The opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the AAMC or its members. The National Center on Disability in Public Health has released a toolkit with talking points and social media graphics to increase vaccine confidence in this population.

Sara*, 22, was doing well until COVID-19 hit. She was working at a café where most of the employees, like her, have an intellectual disability. She’d gotten good at making lattes and had just created a video resume for a Starbucks job. She enjoyed living with her parents in a suburb of Philadelphia and participating in a local program designed to boost independence.

But COVID-19 has created particular obstacles for Sara, who has difficulty communicating, processing information, and adapting to new situations. Some of her therapists have stopped coming to her house, and those who come wear masks that make her feel disconnected from them. She also dislikes how hot her mask feels and how often people remind her to fix it when it slips below her nose.

Then matters got worse. Even though she was careful, Sara contracted COVID-19 and spiked a fever of 104 degrees. Once hospitalized, she struggled to explain how sick she felt. Her doctors spoke very quickly, and by the time she sorted out the questions, they had stopped waiting for her answers. She was confused about why she got moved from one room to another, and she desperately missed her parents, who could not visit her because of COVID-19 precautions.

Sara’s is a dismaying story and, unfortunately, it is not an outlier. I know this well from my experience as director of the Center for Autism and Neurodiversity at Jefferson Health in Philadelphia and from decades working to help create accessible care for all people.

Approximately 6.5 million people in the United States have an intellectual disability. That means they have an IQ score below 70 and other cognitive limitations that affect their communication, social, and self-care skills. COVID-19 has certainly complicated their existence — but it also has ended their lives at tragic rates.

Consider this disturbing statistic: Having an intellectual disability was the highest independent risk factor for contracting COVID-19, controlling for race, ethnicity, and other variables. It was higher even than age or heart or lung problems, according to a recent paper I co-authored. Also, having an intellectual disability was second only to age for COVID-19-related deaths. The paper — which reported on more than 64 million patients at hundreds of U.S. medical centers — found that those with intellectual disabilities were six times more likely to die from COVID-19 than other members of the population.

Some of the increased illness and death may be related to the nature of intellectual disabilities and the supports they entail. For example, people with intellectual disabilities more often live in group homes; use shared transportation; are exposed to people outside their households, including therapists and other providers; and struggle with precautions like mask-wearing.

But there are aspects of these uneven outcomes that raise serious questions about us as a medical community and as a society.

People with intellectual disabilities — in fact, people with any disability — have long suffered in the world of medicine. In a survey published in February, for example, only 41% of physicians felt very confident about their ability to provide the same quality of care to patients with disabilities. When it comes to treating patients with intellectual disabilities, physicians often prefer to speak with their caregivers despite possible concerns over patient consent. And individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups with these disabilities often face additional obstacles: For example, Latino and Black adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities had worse outcomes than their White peers in several health domains.

Having an intellectual disability was the highest independent risk factor for contracting COVID-19, controlling for race, ethnicity, and other variables. ... Those with intellectual disabilities were six times more likely to die from COVID-19 than other members of the population.

I also worry about how biases and misperceptions about the quality of life of people with intellectual disabilities can seriously impair the care they receive. In one terrible example, Alabama’s guidelines allowed doctors to deny ventilators to some people with intellectual disabilities early in the pandemic. (That guidance was later rescinded.)

Clearly, we have much work to do to improve care for people like Sara during the pandemic and far beyond.

Essential steps for better care

Increasing vaccination

As Tennessee’s recent efforts suggest, vaccination can have a dramatic impact on people with intellectual disabilities. From December 2020 to February 2021, new COVID-19 infections among such individuals and their caregivers dropped roughly 80% in Tennessee, the first state to include people with intellectual disabilities in its initial vaccine rollout.

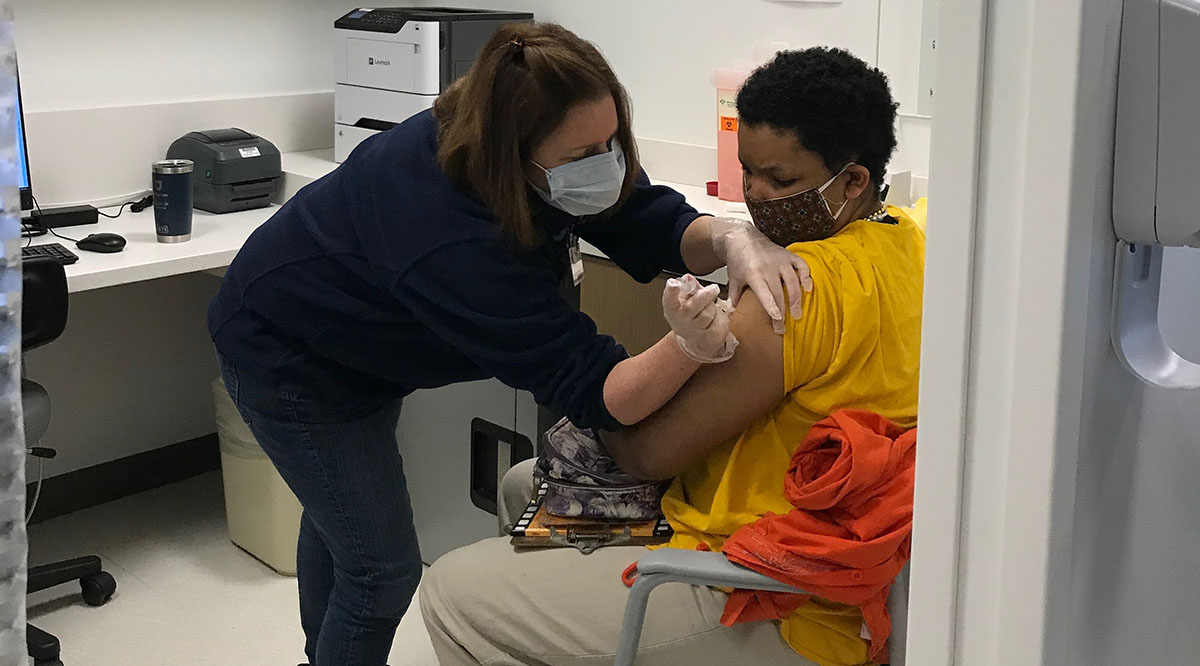

Vaccination for people with intellectual disabilities should include appropriate information for them, such as images depicting the process rather than just words. We need to educate vaccinators about people with intellectual disabilities and how to distract them when they receive their shots, such as providing a squeeze ball. Appointments should be scheduled to reduce waiting, which can be uncomfortable for this more-sensitive population, and recipients should be kept updated as to how soon they can leave.

All this takes time, but it’s worth it. At a recent vaccination event in South Philadelphia, Jefferson Health vaccinated 50 people with intellectual disabilities in six hours and make the event an enjoyable experience for them.

While rapid vaccination of people with intellectual disabilities is essential to protecting this population during the pandemic, much more can be done to enhance the quality of their care moving forward.

Improving education and reducing bias

Curricula across all medical school classes should include relevant information about people with intellectual disabilities. For example, an OB/GYN course should address the fairly widespread myth that this population is usually not sexually active. In addition, standardized patients — trained laypeople who act out medical scenarios — should be used to develop students' ability to interview and examine people with intellectual disabilities appropriately.

Leaders looking to get started can turn to resources from the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry, which also partners with medical schools to help develop curricula.

One impactful strategy is to ask people with intellectual disabilities what matters to them in health care and then share that information with students and providers. Increasing opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities to work in hospitals and doctor’s offices can also help increase understanding and reduce bias.

Providing accommodations and appropriate supports

Although limiting visitors is necessary to reduce the spread of COVID-19, a patient with an intellectual disability may need someone to help them communicate effectively. That often needs to be a long-term caregiver who knows how to read their cues and make them comfortable in ways that even providers educated in intellectual disabilities may not know.

Other possible supports include noise reduction headphones to reduce the stress for people with intellectual disabilities, who may be extra sensitive to loud sounds. Also helpful is preparing these patients in advance for the possibility of hospitalization so their health care wishes are respected. An easy-to-use form, like the one from Stony Brook University, can help patients communicate what makes them particularly uncomfortable and which measures can help.

Becoming allies and increasing awareness

Diversity and equity goals in hospitals and health care systems need to include a focus on people with disabilities.

One key step is to create advisory groups of people with intellectual disabilities who can share their health concerns and suggest ways to address them. In addition, institutions can provide educational sessions that develop these patients’ ability to advocate for themselves. Such moves also help change an institution's culture by making this marginalized population more visible.

Health leaders can also act as allies by taking such steps as urging better insurance coverage for people with intellectual disabilities. Effective care for such patients requires an increased amount of provider time to ensure meaningful communication and care coordination, and that needs to be reimbursed by payers.

Working to increase awareness is also crucial. After our study about the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on people with intellectual disabilities was released, 11 states expanded their vaccine rollout priority groups to include patients with these conditions.

Reimagining Sara’s story

I'd like to imagine a different story for Sara. Perhaps she never gets sick because she’s prioritized for vaccination. If she does get hospitalized, instead of having to just use words, she's given pictures to help her show where she feels pain. Also, one of her parents is allowed to accompany her to the hospital, easing communication with medical staff.

When Sara is discharged, she receives a care plan she understands that is designed to prevent a possible quick return to the hospital. Knowing that their smiles may not be detectable to Sara beneath their masks, the discharge team tells her what a great job she has done in handling this very difficult situation.

*Not her real name