How mass shootings forever change the doctors who respond

The first alert about the horror typically comes from a call, text, or emergency radio transmission that might seem unremarkable: There’s been a shooting; prepare to treat some victims. The initial message often conveys little sense of mass tragedy, no warning that the health care team is about to go through a challenge that will test and change them.

The sense of gravity escalates through updates: It’s an act of mass violence; more gunshot victims than what most doctors, nurses, and paramedics ever see at once; more severe wounds, multiple deaths; more fear in the patients.

“You’re never the same,” says Barbara Blok, MD, an emergency physician at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, who treated victims of the 2012 Aurora movie theater shooting that killed 12 and injured 70.

Christopher Colwell, MD, treated the patients from Aurora, too — 13 years after he walked through Columbine High School in Colorado to examine the bodies of 12 students and a teacher gunned down by two teens. Then associate medical director of the Denver Paramedic Division and Denver Fire Department, he assumed that Columbine was a once-in-a-lifetime event.

“It was lonely,” Colwell says about being a doctor who had responded to a mass shooting. “It is not lonely anymore.”

That’s because mass shootings have become commonplace in the United States, continuously expanding a club that no one wants to join: health care workers who treat the victims. A Washington Post database lists an average of 25 fatal mass shootings a year since 2006, killing a total of 2,527 people and injuring thousands more. (At least four people died in each incident.) They occur in all types of communities: rural, suburban, urban. Many victims of mass shootings are sent to academic medical centers, which house the majority of Level 1 trauma centers and are equipped to handle the most complex surgical cases.

Video produced by Laura Zelaya

Mass shootings set off an all-hands-on-deck response at hospitals, with dozens of doctors, nurses, and support staff treating patients, setting up triage and recovery areas, ensuring adequate supplies (everything from gloves to blood), and coordinating it all.

Six doctors at academic medical institutions who treated victims, in a total of seven mass shootings, talked with AAMCNews about how those experiences affected them. While everyone’s story is unique, many of them share a common arc: the moment of crisis to assess and save victims; emotional struggles for weeks or months; recovery to a new normal with help from colleagues and family; and a changed approach to relating with colleagues and patients, often supplemented by activism to reduce the harm of gun violence.

Their stories offer lessons for health care workers and leaders on responding to and recovering from mass casualty incidents of all types.

Chapter I: The trauma unfolds

People run from gunfire at the Harvest Country Music Festival in Las Vegas on Oct. 1, 2017.

Photo by David Becker/Getty Images

Doctors are alerted and respond

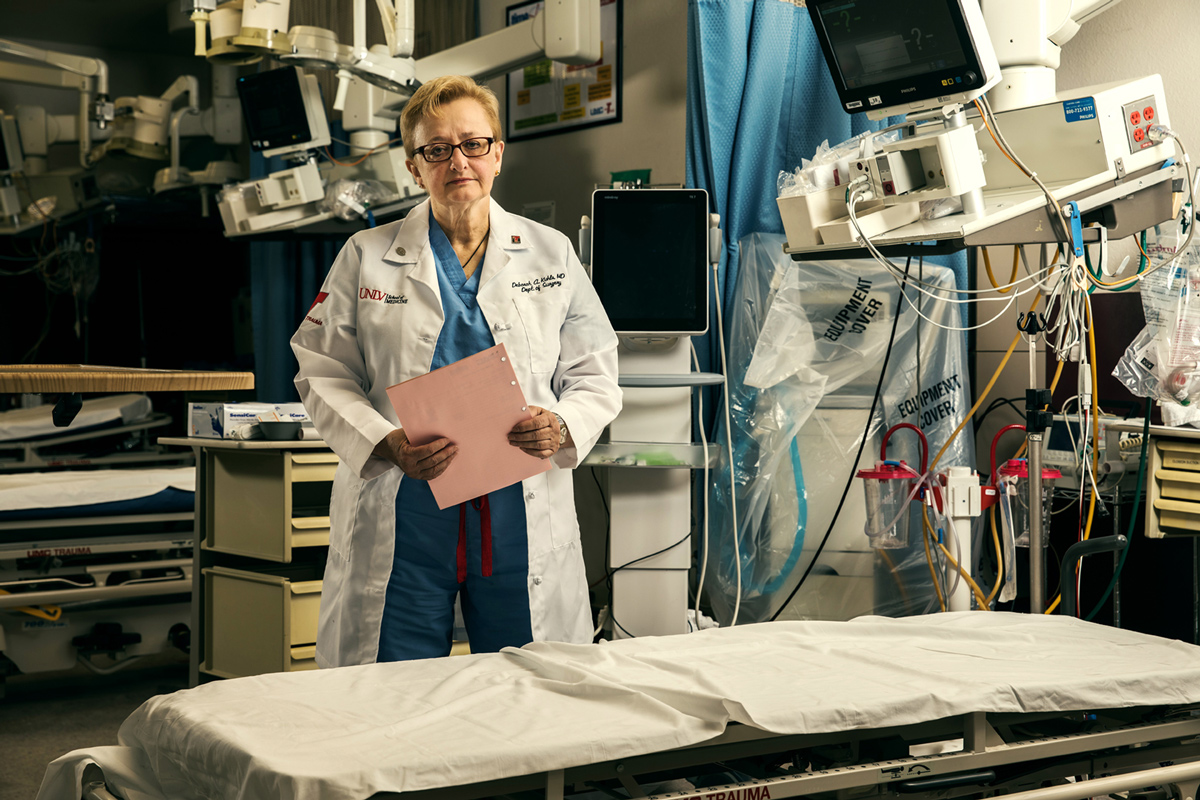

Deborah Kuhls, MD — Las Vegas music festival, Nevada

Oct. 1, 2017, evening — A gunman at a window in the Mandalay Bay hotel fires down into the Route 91 Harvest Festival, a country music gathering of more than 20,000 people. 60 people killed, more than 520 injured.

Deborah Kuhls, MD, at the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada, where as senior surgeon she coordinated the surgical team’s treatment of victims from the mass shooting at a Las Vegas country music festival on Oct. 1, 2017.

Photo by Anthony Mair

Kuhls was the senior surgeon that night at University Medical Center (UMC) of Southern Nevada, in Las Vegas. She is now chief of trauma at UMC, as well as professor of acute care surgery and associate dean of research at the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV.

“A little after 10 p.m. we received an emergency radio message that there was a shooting on the strip. They said we might get a few patients. Then they said five to 10. A minute later, we might get 10 to 20. Then they said we might get 50 or more. This happened within five minutes. Then patients started to arrive.” UMC treated 104 victims.

“Everyone who arrived alive stayed alive. That gave us a lot of emotional relief.”

Barbara Blok — Aurora theater, Colorado

July 20, 2012, evening — At the Century 16 movie theater, a man brandishing multiple firearms shoots at people watching a Batman movie, “The Dark Knight Rises.” 12 killed, 70 injured.

“We heard a dispatch for a shooting at the Aurora theater. We didn’t think anything of it. A short time later we received a phone call from the EMS dispatch center asking how many EMS-transported patients we could handle. We told them five. We had no idea what was happening at the theater.

“The first patient was a young female who had what looked like buckshot [on her leg]. She arrived by private vehicle and walked in. She described what happened in the theater. A lot of shooting, a lot of screaming. She was sitting in the back of the theater; escaped by jumping over a barrier to a hallway from the upper level.

Barbara Blok, MD, walks through the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Blok is an emergency physician who worked through the night caring for victims of a shooting at an Aurora movie theater on July 20, 2012.

Photo by University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

“That was my ‘Oh, no’ moment. That’s when I notified the rest of the team that this is a big deal.”

The ED staff called for available resources, from specialists (surgeons, anesthesiologists) to basic supplies. Patients arrived in droves, usually in police cars and private vehicles, because ambulances couldn’t get close enough to the theater through the crowded parking lot.

“Gunshot wound to the head; gunshot wound to the chest; gunshot wound to the abdomen. They just kept coming.

“We lined patients in hallways. We piled them into our resuscitation area.”

Challenges in caring for the wounded

Mass shootings create special medical and emotional challenges for health care providers. When so many survivors arrive so quickly, it puts the staff and their emergency response plans to the ultimate test. Some victims’ wounds are so severe that they are beyond saving. And some doctors cannot help but identify with the victims.

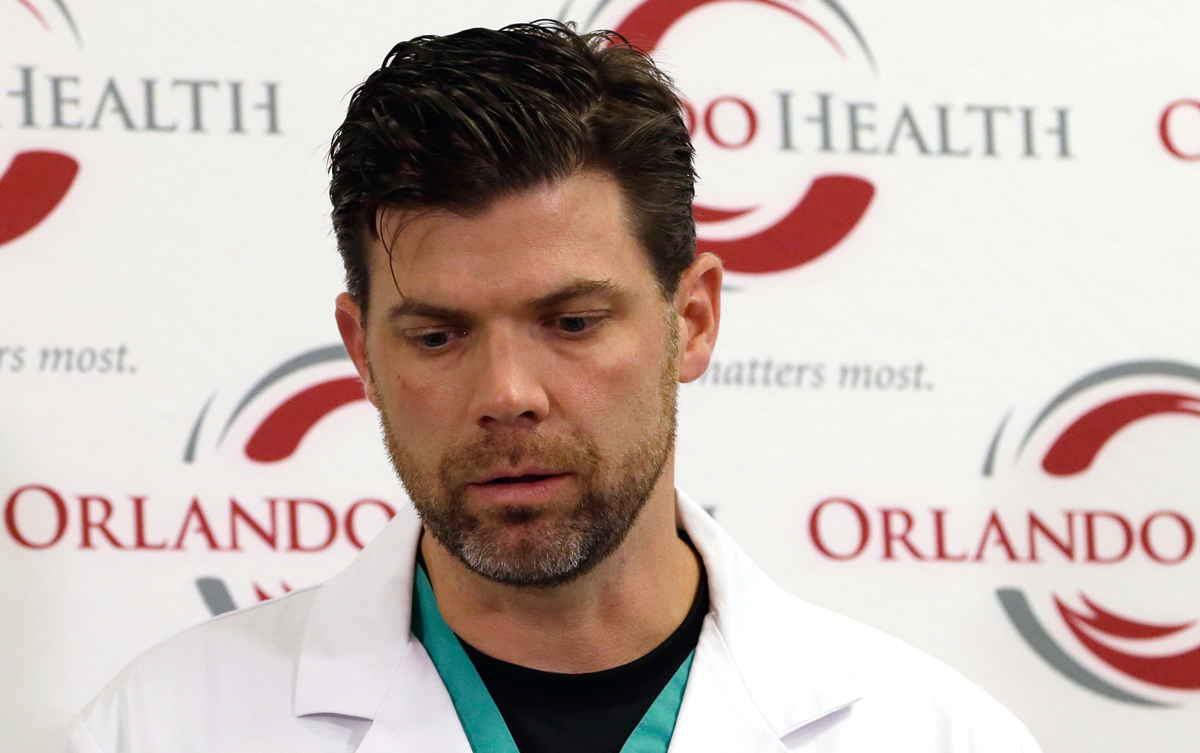

Chadwick Smith, MD — Pulse nightclub, Florida

June 12, 2016, evening – A shooter fires through the crowd at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando. 49 killed, 53 injured.

Smith was the trauma surgeon on call for the ED at Orlando Health Orlando Regional Medical Center (ORMC), which received 44 victims.

“The first patient came in around 2 o'clock, and they came every minute or two. It was something like 36 patients in 36 minutes.”

None of the victims who made it to the hospital alive was lost.

Chadwick Smith, MD, talks with the media at Orlando Regional Medical Center in Florida after treating victims of the Pulse nightclub shooting on June 12, 2016.

AP Photo/John Raoux

Richard Kamin, MD — Sandy Hook Elementary School, Connecticut

Dec. 14, 2012, morning — A gunman walks into Sandy Hook Elementary School, Newtown, Connecticut, carrying several high-powered weapons, including an AR-15 style assault rifle. 26 killed, including 20 children (ages 6 and 7); 2 adults injured.

Kamin was training with one of the SWAT teams he works with in Connecticut when he got a call that there was a shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. He arrived about an hour later. Kamin was and remains an emergency physician at UConn Health in Farmington, Connecticut. His primary role at this incident was to support law enforcement officers and to help other victims on site as needed.

Paramedics informed him that all the victims still on site were dead, as was the gunman. Kamin walked through the school with the paramedics and SWAT teams.

“We went down the hall and into the first classroom. We saw all those children that had been killed. The wounds were catastrophic.

“That was something that I had never experienced. There was no way I could be prepared for this. I just determined that I was going to get to work, and we were going to get through this.”

Richard Kamin, MD, talks at UConn Health about responding to the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, which occurred on Dec. 14, 2012.

Photo by UConn Health

Kamin’s struggles were intensified by the fact that he had children of the same age.

“I felt a unique kind of ache, sadness. Because I had my own kids. I was having images of my kids’ faces on some of the bodies. I was seeing my children with these injuries. It just started rolling through my brain. I was scared. But I put it away because I had work to do.”

Christopher Colwell, MD – Columbine High School, Colorado; Aurora theater, Colorado

April 20, 1999, morning — Two students enter the school with assault weapons and fire throughout the school and outside. 12 students and 1 teacher killed, 2 assailants died by suicide, 21 injured.

Colwell — of the University of California, San Francisco, now vice chair and chief of emergency medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General (ZSFG) and Emergency Medicine at ZSFG endowed professor — was driven to the school from the hospital in a paramedic vehicle to handle triage on the scene. Some victims were sent to hospitals; many were dead.

“I remember vividly walking through the library and seeing the students, some of whom were hiding under desks or chairs. They had been shot in those positions.

“I had never been at a scene of a shooting like this, where there were this many victims. I was the one who pronounced all the victims and the shooters dead.”

Christopher Colwell, MD, FACEP, at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center. As an emergency physician in Colorado, Colwell responded to two mass shootings: Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, and a movie theater in Aurora on July 20, 2012.

Photo by University of California, San Francisco

Focusing on need and speed

The volume of patients and severity of injuries require special consideration about the limited resource of time. Doctors have been trained to do the most they can for each patient. During a mass shooting response, they have to work quickly to stabilize some patients and move on to the next.

Kuhls (Las Vegas): “The usual care is that you get one patient in, we give that one patient our best possible care. But [if we did that for this incident], one could spend a lot of time with one patient while other patients would deteriorate. I switched gears from the everyday occurrences in the trauma center to a mass casualty type of situation, where you want to do the most good for the most number of people.

“We needed to quickly assess patients — who needed blood, who might need the operating room.”

Smith (Pulse): Doctors at ORMC performed 28 surgeries on shooting victims in 24 hours.

“Sometimes, from a surgical perspective, we did the minimum that is required to save someone’s life. We controlled the bleeding. We’d come back in subsequent days to do definitive surgery.”

Fears of active shooter hover over treatment

An occasional concern for health care personnel in the moment is that an active shooter might be on the scene. When doctors and police arrived at Sandy Hook in Connecticut and the Mandalay Bay hotel in Las Vegas, they thought a shooter might still be on site. While staff treated Pulse victims at ORMC, the hospital issued a “code silver,” meaning that an active shooter might be in the building. A doctor barricaded the ED doors with portable X-ray machines.

Smith (Pulse): “One of our interns — she had been a doctor for about 11 months — during that code silver, when we thought there was a shooter in the hospital, it was her turn to go to the operating room. And she wheeled that patient down the hallway, into the elevator, up to the operating room.

“Her and a nurse; thinking there was a madman in the building with a gun. I think about the bravery it takes to do that, the selflessness. Ultimately, there was not a shooter, but you don't know that at the time.”

Emergency plans bestow calm

As patients arrive in droves, emergency preparedness plans and training kick in, enabling staff to focus on their work with confidence. A team atmosphere takes hold: Providers are called in from throughout the hospital and from home; more operating rooms are opened; temporary emergency rooms and recovery areas are set up; and extra supplies are provided from all over the hospital.

Kuhls (Las Vegas): “Our disaster plan mobilized nurses, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists from other areas of the hospital. Our emergency physician knew to go outside to set up a triage area. We had a plan for what to do with the influx of patients. That was absolutely crucial. I was prepared for 50 to 100 or more patients.

“It's a very emotional experience. But my overwhelming thought was how organized our response was. In the heat of the moment, we were able to keep clear minds, make good decisions.”

Chapter II: The aftermath

Doctors, nurses, and first responders pray in the emergency room at Florida Hospital in Orlando, Fla., to honor victims of the Pulse nightclub shooting, which occurred on June 12, 2016.

Photo by Joe Burbank/Getty Images

Immediate impacts

Those who care for mass shooting victims emerge changed to varying degrees. Some absorb the experience in subtle ways; others respond intensely.

Lillian Liao, MD — First Baptist Church, Sutherland Springs, Texas; Robb Elementary School, Uvalde, Texas

Nov. 5, 2017, morning — At the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, a gunman walks in and opens fire during services. 26 killed, 22 injured.

May 24, 2022, morning — A teenager walks into Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, his former school, and fires from an AR-15 style rifle. 19 students and 2 teachers killed, 17 injured.

Liao, a trauma surgeon at the University Health Level I trauma center and at University Health San Antonio, is among the few physicians who have treated victims of more than one fatal mass shooting. Between the shooting at First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs in 2017 and the shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde in 2022, Liao had her first two children. That affected her feelings after treating Uvalde victims.

“It wasn't me as a surgeon that got emotional; it was me as a mom. I went home and I got to hug my kids. I lost it. I felt tremendous guilt because I got to hug my kids. All those parents sent their kids to school this morning, and then tonight, their kid’s not home.”

Liao relives that feeling after learning of new mass shootings; she often tears up when talking about the shootings for which she has treated victims.

“Each time I’ve broken down, it’s me as a mom. It’s hard for me to think about the lives lost. I can’t help it; I start crying.”

Lillian Liao, MD, MPH, a trauma surgeon at University Health San Antonio, talking to reporters.

Photo by University Health San Antonio

Kamin (Sandy Hook): “The next day I started wondering if I was broken. Am I going to be able to continue being a dad, continue being a husband, continue being an emergency physician, continue doing the work that I had found unbelievably satisfying?”

Smith (Pulse): “I did cry on the drive home. There were nine people that were brought to the emergency department that didn’t make it out of the emergency department.

“I went outside and saw we had moved all of the decedents to our decontamination area — it’s a bay where we can pull a curtain around it. There are nine people in there who just went to a nightclub, and they are not coming home.”

Blok (Aurora): Like most of the staff, Blok worked through the night and went home the next morning. She was told that the pastoral care team was going to hold a debriefing for staff to talk about the experience and their feelings.

“I didn’t feel like it. There was just too much. I was exhausted. I went home and slept for a little bit, then went out hiking, just trying to process everything.

“I was working again that night. People said, ‘We can work for you.’ I said no. I should go back and be with the team, try to normalize this a little.”

Things did not normalize for years.

“I didn’t meet all the criteria for PTSD, but I had a lot of the symptoms, like emotional, intrusive thoughts, where I’d be doing something random and suddenly the thought of that shooting would come into my head.

“I’m thinking, I’ve taken care of gunshot wound victims many times. Why is this harder?”

Getting help from others

Talking with colleagues and friends has proven essential to getting back to a new normal.

Kamin (Sandy Hook): Back at home that night, Kamin got a call from the chair of his emergency department, Robert Fuller, MD. Fuller is widely recognized for his work on disaster response, including treating victims of an earthquake (Haiti), a typhoon (Philippines), and the 9/11 attacks (New York).

“He told me, ‘It may be hard to concentrate. You may have intrusive thoughts. It may be hard to sleep. You may be more irritable.

“’You need to do your best to get some sleep. You need to exercise every day. You need to eat well. Don't use any drugs or alcohol to deal with what's happening. I have taken you off the clinical schedule until you're ready to come back.’”

Fuller picked up Kamin at 7 the next morning to go to the gym together.

Smith (Pulse): For Smith, the full awareness of what he’d been through didn’t kick in until weeks after the Pulse shooting, when he and his wife went on a planned vacation to Los Angeles to celebrate their anniversary.

“I met with a colleague who used to be one of our trainees, and he had been in Iraq, in the Navy. We sat and had breakfast one morning together and talked for two or three hours just about the raw emotion of it all.

“He's like, ‘You sound like you've been to war. That's what I felt like in the Battle of Fallujah.’ I have the utmost respect for our service members, I don't want to compare myself to that. But those were his words. … You feel like there’s a hole in your chest.

“When I got back from our anniversary, walking into the hospital — I did not want to be at this place. That took months to go away.”

Formal debriefings are powerful

Several hospitals set up formal debriefings, where frontline staff, supervisors, mental health professionals, and chaplains talked about the experience and how to deal with thoughts and emotions. On Tuesday morning at UMC, a little more than one day after the concert shooting, the chair of psychiatry facilitated a gathering with everyone in surgery who wanted to join.

Kuhls (Las Vegas): “We spent two or three hours talking about how we were doing. Some people seemed fine; some had a hard time talking about it. They couldn’t imagine how someone could do this.”

Community support uplifts spirits

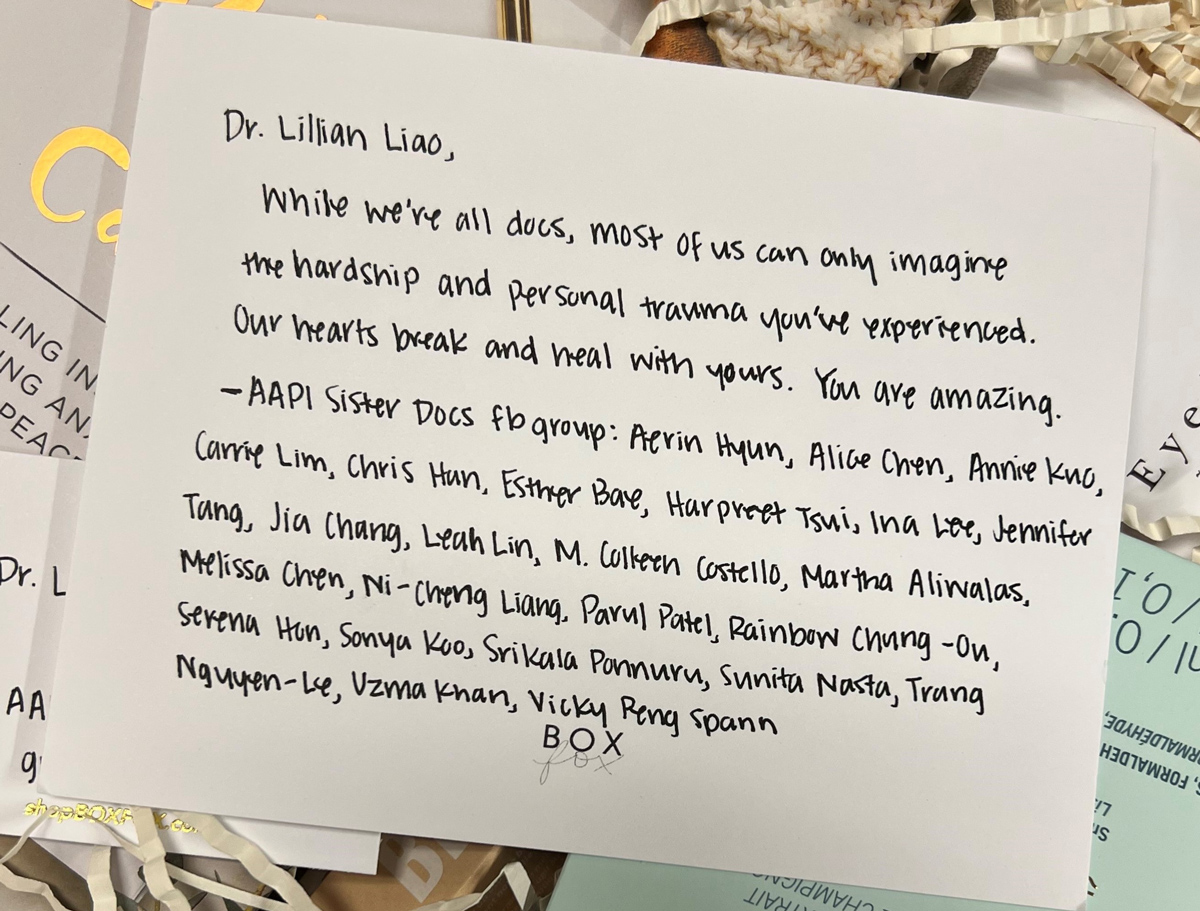

Acts of support from health care workers and from the community at large are helpful after a mass shooting. After Pulse, hospital systems from around the country sent Orlando Health decorative banners with bright colors and messages of support, signed by their staff. Those were hung up in common areas of the hospital. Liao has gotten hundreds of cards and letters offering praise, gratitude, and prayers — most from people she didn’t know, and often after seeing her cry during TV interviews about the Uvalde victims. (Liao teared up during two interviews for this story.)

A note from fellow doctors included in a care package Lillian Liao, MD, MPH, received shortly after treating victims of the Uvalde school shooting.

Photo by Lillian Liao, MD, MPH

Liao (Sutherland Springs; Uvalde): “I've never been trained in media interviews. I think I should try to stop crying.”

A group of women physicians, whom Liao didn’t know, sent her a wellness basket of facial care products and chocolate. She joined their Facebook group.

“It was therapeutic for me to read those. When you go through a mass casualty, it feels like the world is dark and horrible. The letters bring back that positive view of the world. I still have them in a pile. It reminds me of the good in people.”

Kuhls (Las Vegas): “The community response was overwhelming. The most impressive thing was, as I crossed a street leaving the hospital, there were all these people lined up at an ancillary building. It was a pop-up blood donation center. My recollection was that there were a thousand people waiting in line to donate. The entire block of our hospital was outlined in [donated] crates of water bottles.”

Chapter III: Forever changed

Roy Guerrero, MD, a pediatrician who lost patients in the assault in Uvalde, Texas, speaks at a rally in Washington, D.C., in 2022 about gun violence.

Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Many doctors who respond to fatal mass shootings change in ways both personal and professional. Some changes are subtle, as in their approach to patients and colleagues. Some steer their careers toward activism about gun violence and disaster preparedness.

Blok (Aurora): “You're never really the same. You don't think about it every day, but it's a part of you. And you wish you didn't have that as part of your memory.

“It took a long time to totally recover. When I think about it, I can still feel that anxiety rise or the sadness that I felt for weeks and months afterward. When I present a lecture about the shooting, it makes me emotional.”

Kamin (Sandy Hook): “I am absolutely a different person than before I walked into that school. And things have normalized. And I still am a dad and a husband and a physician, and doing all of these things that I had been doing before. To some degree, I might be better at doing them. I have become a differently empathetic and compassionate individual.”

Blok (Aurora): “It's a new normal, which is OK. Maybe it's made me a little bit more empathetic and understanding of people who have gone through trauma.”

“I still cry when I think about it sometimes. The anxiety will come back if I hear about a mass shooting.”

Helping doctors after mass shootings

After another mass shooting occurs, doctors who’ve been through the experience often reach out to those who just went through it to talk about how to handle the emotional and logistical challenges. Colwell sends a text or leaves a voicemail.

Colwell (Columbine, Aurora): “’I’ve been through it. Let me know if I can be helpful.’ To reach out and say, ‘These are probably some of the things that you might be feeling right now. Totally normal. This is how they might evolve. These are things to be aware of, be careful of.’”

Blok, in Colorado, counseled a colleague overseeing staff who responded to a bombing in Beirut, Lebanon.

After the mass shooting at the Kansas City Super Bowl victory parade in February 2024 — 1 person killed, 22 injured (including 11 children) — several veterans of mass shootings held a group call with doctors at hospitals in that city. The call was arranged through the Eagles, a coalition of emergency medical directors.

Colwell (Columbine, Aurora): “They [the Kansas City doctors] said they were struggling. One was a residency director. Some of the residents had been on the scene at the parade. She was wanting to find the best way to support the residents in the immediate aftermath.”

Speaking, teaching, and writing

The shootings have shifted the careers of some doctors. They feel a responsibility to share the experience and lessons.

Some (such as Colwell and Kuhls) have become experts in emergency preparedness and disaster planning, helping to develop curricula, studies, and plans. More than a half-dozen physicians participated in a project by the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine to produce a survival packet for leaders to prepare for mass casualty incidents and the aftermath. Many doctors who’ve responded at these incidents routinely speak at conferences and other gatherings of medical professionals and students about the experience in the moment and lessons for caregivers and hospitals. Blok, in Colorado, presents lectures on lessons from such emergencies, including that “PTSD symptoms are normal.”

When reporters call to talk about another shooting, they try to oblige.

Smith (Pulse): “I do media interviews because I want to get the message out; help organizations realize that disaster planning is important, and you have to practice. In today’s world, the chances are not so low that you have to plan for a mass shooting.”

Advice to providers and leaders

Colwell (Columbine, Aurora): To frontline workers: “It will be part of your identity for the rest of your career. You can choose how that part of your identity looks, and you can help craft it into something that's a positive or you can let it take you over.”

To health care leaders: “Recognize that some of your people are going to respond immediately and be clearly in need of help then, and others are going to look like they are absolutely fine. Months later, they will start to really be impacted. Be aware of your people. Watch them.”

Kamin (Sandy Hook): “For a long time, I felt like I wasn’t growing out of this. I was feeling like I was walking with a limp and I worried that it was going to be forever. I remember the relief I got when the first person said, ‘You're not going to limp forever.’”

“What worked for me was being unbelievably lucky to have qualified colleagues telling me what to expect, giving me suggestions about what I could do, and assuring me that I wasn’t broken.”

When Kamin hears of another mass shooting, some of the upset feelings return, although less severely as time passes.

“If I were not affected every time one of these happens, I would start questioning my humanity.”

Story Credits

Written and reported by Patrick Boyle

Video produced by Laura Zelaya

Executive Producer: Gregory Gilderman

Executive Editor: Gabrielle Redford

Executive Digital Producer: Issa Chan

Digital Producers: Laura Kinneberg and Nick Simson

Video co-producers: Matthew Fredericks, Marco Duran, and De'Angello Powe

Photo Editor: Mukti Desai

Copyeditor: Elena Marinaccio

Communications: John Buarotti

Project Manager: Vicky Valery