They say that medicine is as much an art as a science. But for some extraordinarily talented medical students, their artistic pursuits have informed not only their practice of medicine but also their choice of specialty, their ability to empathize with patients, and their desire to help others.

Take, for example, Julia McMillan Castellano, 34, a professional dancer in New York City who has been able to continue dancing throughout medical school at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. “Doing something that we’re passionate about can remind us why we do what we do in medicine,” says Castellano, who plans to pursue a career in pediatrics. “Often that’s to help other people become their healthiest selves so that they can pursue their passions.”

AAMCNews interviewed seven fourth-year students who shared how they successfully combined their artistic endeavors with their medical school training, and how the arts and humanities helped shape the future doctors they’ll become.

Grace Li, 28

Stanford University School of Medicine

Writer

Specialty: Emergency medicine

Matched: Mass General Brigham

Grace Li still remembers a moment in elementary school when her parents had a meeting with the school librarian. “They were worried I was reading too much, and not spending enough time making friends,” Li recalls with a laugh. “I just really loved stories.”

That passion for the written word led Li to minor in creative writing at Duke University (she majored in biology), where she finished her first novel between Organic Chemistry classes. Writing was an opportunity to stretch a different aspect of her brain, but after finishing the novel, she determined it “wasn’t very good,” and set it aside.

After graduating from college, Li started working as a high school biology teacher in the Bronx as part of Teach for America. That experience solidified her desire to become a physician. “Many of my students didn’t have reliable access to health care, and so they were asking me [about their health]. … I just wanted to be able to answer my students’ questions.” She finished a second novel during that time, and began considering what being a published author might look like — while also applying to medical schools.

Li began medical school at Stanford in 2019. She had started writing her third book by then, an Asian American heist story that would ultimately become Portrait of a Thief. Inspired by a true story, it follows five college students hired to steal back looted Chinese art from museums around the world.

The novel sold during Li’s second year of medical school, and it became an instant New York Times bestseller and Edgar Award nominee when it was published in 2022.

Li has since written another novel, Anatomy of a Betrayal, coming out in 2025, and is under contract to write several more — even as she eagerly waits to discover where she’ll match into emergency medicine. She views writing and medicine as different but complementary: both are ways to make meaning of the world.

“This past week, I've been wondering which was more stressful — submitting my book to editors or submitting my rank order list and waiting for Match Day,” Li smiles. “I don’t know, but I feel very lucky to have two careers I love so much.”

Julia McMillan Castellano, 34

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Dancer

Specialty: Pediatrics

Matched: NYU Langone Health

Julia McMillan Castellano started dance classes at age 3. “I simply don’t know life without dance,” says the fourth-year student at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

In fact, Castellano danced professionally in New York City for six years after college, and had impressive success. In 2017, she was nominated for a Bessie Award for Outstanding Performer, one of the highest honors in the New York City dance world. And she garnered some stellar reviews: “The effort and the concentration that [Castellano] maintains redefine virtuosity,” wrote one critic of her performance in an intensely precise modern dance piece.

But recognizing that her body might not always weather dance well, Castellano began considering alternatives. Health care was at the top of her list. But during college at Manhattan’s Tisch School for the Arts, Castellano had set aside science. “I took no chemistry, no biology, almost nothing medical schools want,” she says.

So in 2017, she enrolled in a postbaccalaureate program to fill in the gaps — and loved it.

Once in medical school, Castellano continued to dance professionally even though finding time wasn’t simple. She managed, in part, by rehearsing on weekends and strategically using an occasional allowed absence during clinical rotations.

The effort was certainly worthwhile, she says. “For me, dance and medicine are inextricably intertwined. There isn’t one without the other.”

For one, dance fuels her emotional well-being. “It’s a chance to completely turn off my medical school brain,” she says.

Castellano also believes that art improves patient care. “Doing something that we’re passionate about can remind us why we do what we do in medicine. And often that’s to help other people become their healthiest selves so that they can pursue their passions.”

Looking ahead to residency in pediatrics, Castellano hopes to emulate a doctor who treated her scoliosis when she was 12. Approached for a second opinion, that provider enabled Castellano to avoid surgery that likely would have precluded a career in dance. Years later, she still profoundly appreciates how seriously the doctor took her dance-related concerns. “That doctor changed my life,” she says.

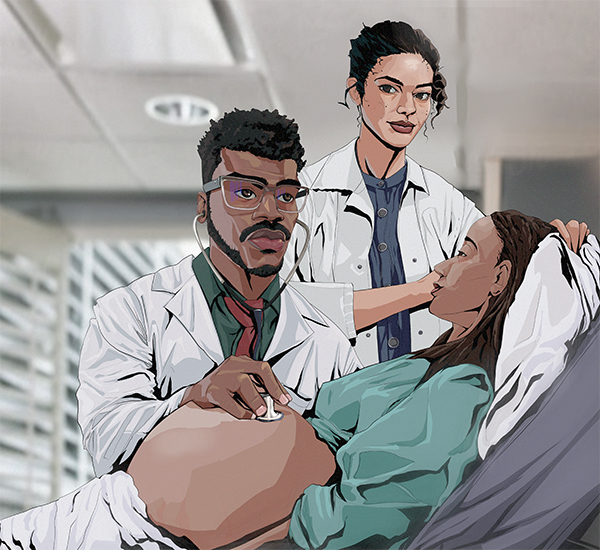

Arinze Ochuba, 26

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Digital artist

Specialty: General surgery

Matched: Temple Health

Arinze Ochuba has always been a doodler. From his childhood in Nigeria when he would spend evenings on the porch drawing to winning school drawing contests to sketching the faces of medical school classmates, art has been a way to express not only his ideas and thoughts but also his emotions.

That was particularly important during the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic. After emigrating with his family to the United States when he was a teenager, Ochuba started medical school at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in the summer of 2020, before the arrival of the mRNA vaccines, which meant that most classes were online and the opportunities to interact with medical school peers were limited.

“The isolation hit us a lot,” he says. “It hit people differently and my experience differs from everyone else’s but … there was some human element that was missing. And so my art, in a way, helped me to placate all of those feelings of loneliness and isolation.”

Ochuba decided to try his hand at digital art, which he taught himself in 2020 through watching YouTube videos. “Digital art doesn’t differ too much from traditional art in the sense that you still have to draw whatever it is you’re putting down on paper,” he says. “But it cleans up easier.”

Since then, he has drawn mostly people — friends, mentors, people he sees on the street. “I’m a big proponent of the idea that life imitates art and art imitates life,” he says. “And what is the most interesting and intricate, beautiful creation? The human body. It is literally biological architecture.”

Ochuba knows he might not have much time during residency to continue his art. “My first priority is to my patients, making sure I can give them the best care that I can,” he acknowledges. But, he’ll try to doodle during rounds, at the very least. “That [will help] me to satisfy that need to sketch something,” he says.

Omar Hamza, 26

Texas A&M University School of Medicine

Musician

Specialty: Psychiatry

Matched: Cambridge Health Alliance

Omar Hamza finds refuge in making music. He began recording songs in his bedroom as a teenager, when he struggled to rectify within himself the Arab culture of his family (his father was born in Syria, his mother in Palestine) with the rural American culture of Port Neches, Texas, where he was raised.

Part of him was typical American boy — he enjoyed fishing and hunting — but “at the same time, I had this Syrian culture behind me, and it felt like some people were hostile towards it.”

Hamza started playing his guitar and recording his compositions on his phone — soft songs about love and heartbreak, sung in English and Arabic, and occasionally posted on YouTube. “When I made music, it was like making peace with that cultural divide,” he says.

While attending Lamar University in Texas, a medical mission to Syria inspired Hamza to become a doctor and focus on psychiatry. “There is a massive shortage of psychiatrists in all Arab communities,” he explains. By the time he reached medical school, his hobby of posting music had faded out … until the stress of his studies compelled him to revive it to fend off burnout. He started recording songs in his room with a guitar and keyboard, posting some on TikTok.

“I didn’t expect anyone to listen to them,” he says. Then one song got thousands of hits, and he developed a following. He’s posted two dozen songs across several platforms, including Apple Music and Spotify, collectively reaching more than one million listeners.

“Posting my compositions ended up being a means of connecting with hundreds of thousands of people who struggled with a similar sense of identity crisis,” Hamza says. “Each song is a reflection of my journey, blending elements of my Syrian and Palestinian heritage with the experiences and influences of my American upbringing.”

Hamza plans to continue recording through residency. “Music has been a lifeline,” he says.

Samantha Maisel, 31

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Ceramic artist

Specialty: Emergency medicine

Matched: UCLA

Samantha Maisel sees endless similarities between medicine and her art.

For one, her chosen specialty — emergency medicine — is hands-on, in much the same way as shaping and molding clay into beautiful mugs and bowls is. “I love suturing and procedures … I want to make someone’s sutures the best that I can.”

The emergency department is also unpredictable from day to day — it’s the place where people from all walks of life go to seek care, whether it’s primary care or a heart attack or a traumatic injury. Likewise, Maisel specializes in high-fire ceramics, a style of pottery where each piece is thrown and glazed and fired at such a high temperature that she’s never quite sure what will emerge from the kiln at the end of the day.

“You really have to let go a little bit and embrace the imperfections that come out. [And recognize that] it's the imperfections or the little fingerprints that make it really special,” she says.

Maisel credits her mother, who was a dentist by training, with instilling in her five children a love of the arts. Maisel took her first ceramics class in high school in San Diego, and then followed that with classes during college at the University of Michigan and Wesleyan University. After earning her undergraduate degree at Wesleyan, she did a masters in neurobiology, then took time off to work on an herbal farm in Oregon, and later in a lab at the University of California, San Francisco, working with patients to enroll them in clinical trials for gastrointestinal cancers.

It was that last experience that convinced Maisel to enroll in medical school.

But all along the way, she found time and space for her pottery. “Every place I’ve landed, I’ve tried to find a ceramics home,” she says. “There’s something really healing about touching clay, when I’m making it and even afterwards. Having my hands in clay is my medicine and something I prioritize.”

While she mainly sells her pottery to family and friends, Maisel has occasionally sold at craft fairs. And she’ll continue making and selling her pottery @potsbysami during residency and beyond, knowing that working with clay will help keep her grounded amidst future challenges.

Hayden Guidry, 25

LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine

NFL Cheerleader/dancer

Specialty: Otolaryngology

Matched: University of California, Davis

The little girls needed a boy. Their dance class was putting together a routine from Grease for a local competition, and the routine included a small part for Danny, the character played in the movie by John Travolta.

The dance instructors drafted 8-year-old Hayden Guidry, who routinely hung around the studio because his younger sister was in the class. The dance performance won first place.

Soon, Guidry was taking dance lessons and racking up first place finishes — all the way through high school, where he was dance team captain.

“Dance was a saving grace in my life,” he says.

That’s because Guidry sensed that he was somehow different from other kids in his hometown of Lake Arthur, Louisiana.

“Dance was my way to express myself, to explore who I was as a person at such a young age,” he says. “The dance studio was my safe haven.”

He stopped dancing when he attended Louisiana State University so he could focus on academics and getting into medical school — motivated by wanting to improve people’s lives, and eager to earn the respect that would make him confident to come out as gay, which he did in his senior year of college.

But after his first year of medical school, Guidry says, he “started to feel a kind of emptiness.” Now comfortable as openly gay, he began to question whether medicine was the right career choice — and whether it had been worth giving up dance to pursue academic success.

“I had pushed aside part of myself in the pursuit of medicine,” Guidry says.

He started attending a local dance studio, where he met members of the New Orleans Saints cheerleading team. Impressed by his moves, they convinced Guidry to try out. He was one of 53 dancers chosen for the 2022-23 season.

“Rediscovering dance was a turning point,” he says.

“I was able to develop my own motivations to pursue medicine — connecting with people and being able to tell their stories. My favorite part of dance is the ability to tell stories with your body, and one of my favorite things about medicine is allowing your patients to tell their stories. That’s by listening and talking.”

Wherever his residency is located, Guidry plans to find a dance studio.

Richard Wu, 27

University of Texas Southwestern Medical School

Artist and writer

Specialty: Psychiatry

Matched: Johns Hopkins Medicine

At first, Richard Wu wasn’t sure he’d pursue medicine. During college at the University of Texas at Dallas, numerous subjects appealed to him: creative writing, biochemical research, architecture, even mechanical engineering.

Ultimately, Wu chose medicine because it was both an art and a science. “Doctors need to understand biology, but understanding a patient’s personal story is also crucial to clinical care,” he says.

Wu is now a fourth-year student at University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, but he never set aside his creative pursuits. And the native Texan’s art ranges widely. He has produced a sci-fi short story, poems about loss, ink sketches inspired by Cubism, architectural photos, and a whimsical, smiley-faced illustration, to name just a few.

Wu’s writing and art have been published in such venues as Nature and Bellevue Literary Review, and he’s been nominated for the prestigious Pushcart Prize. His artwork has even been exhibited in the U.S. Capitol.

He believes all this creative activity makes him a better doctor.

Wu, who plans to study psychiatry, notes that a growing body of research suggests that the humanities enhance the practice of medicine. “The arts heighten observational skills, improve empathy, and reduce burnout,” he explains.

Personally, Wu finds that art and writing have helped him develop a keener appreciation for different perspectives: “It’s important to understand that in the same situation people can have very different experiences. A doctor may see it one way, and the patient may see it another.”

Looking ahead to residency, Wu recognizes that he may have to set aside his creative pursuits at times. But he hopes to turn to them as often as possible given the role they play in helping him process the suffering that physicians inevitably witness.

Wu points to invaluable advice he received when entering medical school: “Make sure to schedule your joy. It may feel selfish, but it’s not, because in the end, it helps your patients too.”

________

The AAMC has a longstanding initiative to support the integration of the arts and humanities in medical education. Find more resources on the Fundamental Role of Arts and Humanities in Medical Education (FRAHME) website.