Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of articles about trust in science. Subsequent articles addressed whether the iterative nature of scientific discovery is at least partly to blame, why so many people believe medical misinformation, and whether people can be immunized against disinformation.

Medical science is creating miracles and losing trust. It’s emerging from the darkest days of the pandemic with both lifesaving discoveries and a crisis in credibility.

Although confusion and hostility are defining features of the past two years of COVID-19, the crisis of trust in our society didn’t start with COVID-19 and won’t end with COVID-19. It’s not about a disease, it’s not about Twitter, it’s not about facts alone.

“It’s not just a COVID thing,” warns Steven Joffe, MD, MPH, interim chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

Rather, the pandemic provided a fertile environment for myriad social and technological forces to breed confusion and distrust. Those forces ignite epidemics of misinformation against pillars of society: among them our systems of justice, education, science, and democracy.

“Trust in scientific institutions has taken a huge hit,” says Timothy Caulfield, LLM, research director of the Health Law Institute at the University of Alberta, Canada.

“The whole strength of science is that people who have different ideological bents can do experiments, transcend their prior beliefs, and try to build a foundation of facts,” says Janet Woodcock, MD, principal deputy commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). “Now we have whole groups of people who don’t believe that.”

Moving forward, scientists working on high-visibility health projects are more likely than ever to find themselves operating within an infodemic: an overload of information about a problem, much of it wrong, that makes it harder to solve the problem.

Science leaders in government and academia say that meeting the challenge to regain credibility requires a deeper understanding of several conditions:

The forces and factors behind distrust, which include a public overwhelmed by too much information, growing polarization, disinformation campaigns by domestic or foreign corporations and governments, a media environment that rewards outrage and outlandishness, and the increasingly public nature of scientific research.

The people who spread and who absorb misinformation, who include those who set out to find the truth but get confused or outraged by misinformation they stumble into; conspiracy theorists who gravitate toward stories that confirm their suspicions; and organized groups that peddle disinformation for profit.

The motives behind disinformation, which is a form of misinformation that is deliberately deceptive. Those motives include politics (arousing opposition to the other side), profit (making money by pushing bogus scientific products), social advocacy (raising support for a cause that cuts against the scientific consensus), and even foreign affairs (sowing distrust in an adversary’s government). For example, reports by the European Parliament and the Center for European Policy Analysis concluded that Russia and China spread disinformation about COVID-19’s origins and COVID-19 vaccines in order to convince people in democracies that they “cannot trust their health systems” and to “exacerbate tensions” in Western governments.

Disinformation strategists “are weaponizing scientific uncertainty and trying to create distrust,” says Caulfield, a law professor who studies those strategies. “They’re trying to create information chaos.”

The harm to science and the public

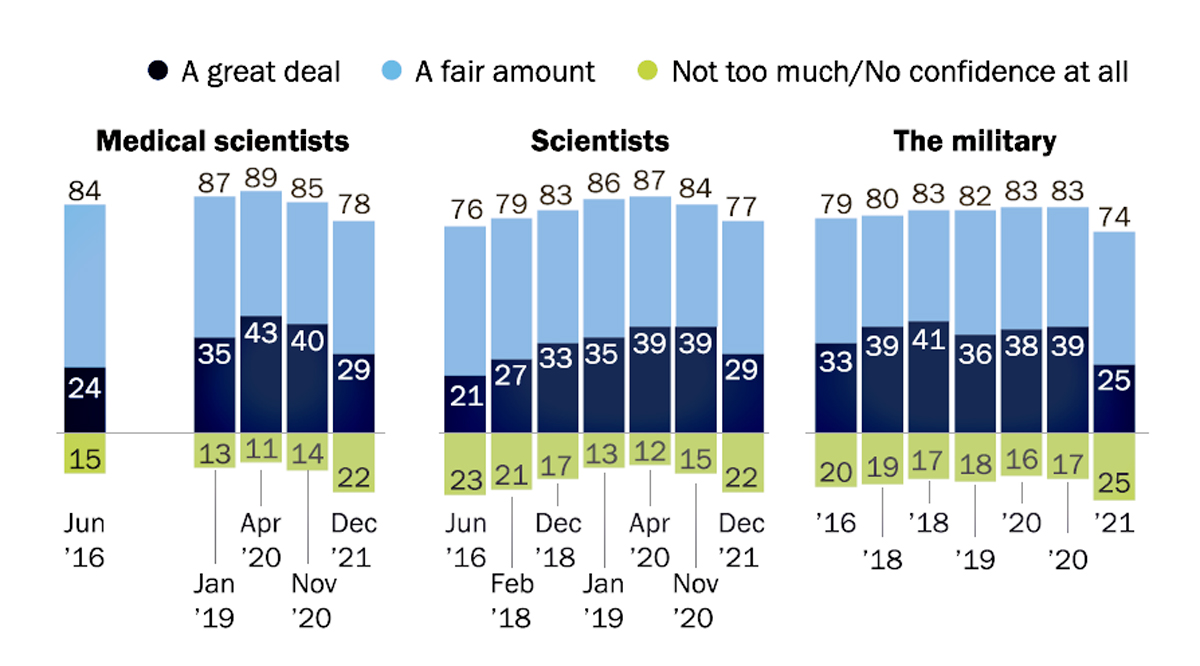

When it comes to measuring the impact of the attacks on medical science, opinion polls have, ironically, produced results that confirm what anyone wants to believe. Some polls show that “science” and “medicine,” defined broadly, retain high overall trust in the United States, right up there with the military.

Where people turn skeptical is when scientists draw conclusions about issues that pluck sensitive chords — namely, telling people what to do. The Pew Research Center reported in February that 29% of U.S. adults say they have “a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the best interests of the public,” down from 40% in November 2020 and below the ratings before the coronavirus emerged.

Public confidence in scientists and medical scientists has declined over the last year

% of U.S. adults who have __ of confidence in the following groups to act in the best interest of the public.

Credit: Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (February 2022)

Credit: Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (February 2022)

One troubling consistency, demonstrated in this poll by Gallup, is that Republicans have been losing trust in medical science for years while trust among Democrats holds steady. The more people see science as another politicized field — as many people see the movie industry and mainstream news — the more they will dismiss scientific findings that clash with their worldviews.

“We now have a significant minority of the population that’s hostile to the scientific enterprise,” says Sudip Parikh, PhD, CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). “We’re going to have to work hard to regain trust.”

Lack of trust in health authorities can hurt people. The U.S. Surgeon General and the World Health Organization (WHO) have declared that health misinformation is a threat to public health because it leads people to ignore science-based recommendations about behaviors to practice and to avoid.

At the FDA, Woodcock sees risks even to basic communications about food and drug safety: “If we say, ‘This food additive is safe,’ there are going to be people who just say we don’t have any credibility. There will be people who say, ‘They're lying.’”

On a global scale, scientists fear that the spread of misinformation will make it impossible to successfully meet other public health challenges: pollution, climate change, and future epidemics, among others.

Confidence in Science, 1975 and 2021

Now I am going to read you a list of institutions in American society. Please tell me how much confidence you, yourself, have in each one -- a great deal, quite a lot, some, or very little? How about -- Science?

Credit: Gallup

Credit: Gallup

Forces and factors that drive distrust

A mix of cultural conditions, sophisticated strategies, and electronic communication mechanisms are feeding on each other to undercut the credibility of medical science. These factors and forces overlap.

People are overwhelmed by information coming through their computers, phones, and televisions. Sometimes they can’t sort out all the breaking information about critical health issues.

Even Lindsey Leininger feels it. Leininger is a public health scientist and co-founder of Dear Pandemic, an online forum created to help people “navigate the COVID-19 information overwhelm.”

She’s also a mother trying to protect her children. “There’s all this decision fatigue” for parents, she says. “Should my kids wear masks to school even if they’re not required? Should I get them vaccinated?”

People “don’t have the bandwidth to do the analysis” of countless health studies and news reports that come through all forms of media, says Leininger, a clinical professor of business administration at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business in New Hampshire.

Complicating the task is that some of the misinformation is designed to confuse and divide people. “One way to do that is to flood the zone with falsehoods and conspiracy theories, and to cause mass disorientation,” notes journalist Jonathan Rauch, who recently published a book about information warfare, The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth.

Uncertain about how to tell what’s true and false, Leininger observes, people rely on proxies to guide them: “You say, ‘This is not my expertise. I’m going to rely on somebody whose expertise this is. Who are the people I trust? What do they say?’”

Leininger turns to peers in science. Those not in science turn to trusted TV personalities, bloggers, friends, and community leaders — who might share their social and political values and assess the information through those lenses.

The country is growing more socially divided and politically polarized. Polls such as this one confirm what Americans feel.

As a result, people increasingly get much of their information about the world — politics, science, foreign affairs, and more — from people and institutions that confirm their beliefs, and ignore sources that run contrary to those beliefs. This harms health efforts.

“Misinformation tends to flourish in environments of significant societal division, animosity, and distrust,” says the Surgeon General’s advisory.

The divisions and distrust make people more open, even eager, to accept information that discredits the beliefs of people on the other side.

“They like feeling part of this community,” Diane Benscoter, founder of a group focused on psychological manipulation, told a recent conference on Disinformation and the Erosion of Democracy. “When you give them facts that say, ‘It’s big medicine, big pharma, big corporations feeding you lies,’ they want to believe it’s lies.”

Climate change illustrates the struggle to win over skeptics in a polarized society. Many liberal leaders have zealously taken up the cause of combatting climate change as a core issue. Conservative commentators have responded with fury and stoked fear in their audiences. The clash has spiraled to the point where the science doesn’t matter as much as the politics, as each side feels that agreeing with the other would constitute abandoning their tribe.

“Perhaps the most serious threat to science is the politicization of scientific facts,” Vera Donnenberg, PhD, associate professor of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told the AAMC’s annual Learn, Serve, Lead conference last year. “Once a scientific issue becomes politicized it gains its own life.”

Trust in institutions is eroding. All government and private institutions that develop health policies suffer harm from news reports about research scandals (such as fraud), conflicting findings among scientific studies, and dismissive pronouncements that everyone should “just trust the science.” As Jonathan Haidt, PhD, a social psychologist at the New York University Stern School of Business, wrote recently, “When people lose trust in institutions, they lose trust in the stories told by those institutions.”

In Vaccine Hesitancy: Public Trust, Expertise, and the War on Science, Maya Goldenberg, PhD, a philosophy professor at the University of Guelph in Canada, contends that some people oppose vaccines in general not because they don’t know enough about science but because they don’t trust the institutions that recommend vaccines. “Vaccine hesitancy signals a crisis of trust between the publics and the institutions that structure civic life,” she tweeted.

When it comes to COVID-19, some researchers found that in countries where citizens reported high levels of trust in their government institutions overall, people were more likely to follow mitigation efforts such as masking and getting vaccinated. At the same time, however, the ever-changing scientific knowledge about the disease triggered confusing and sometimes contradictory messaging from authorities, which reduced trust.

Adding to the erosion is increased access to scientific research (see more below), which allows people to find science that supports what they want to believe. When everyone can become their own expert, it’s easy to waive off declarations from science institutions as flawed or driven by hidden agendas.

Faux experts undercut the scientific consensus. Perhaps the most common tactic of disinformation campaigns is making people doubt that scientists have reached a consensus on an issue, says Sander van der Linden, PhD, a social psychology professor at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. All it takes is providing a few people of questionable expertise to disagree with all those credible experts.

“We can say thousands of scientists agree, but they say here are all these important people who disagree,” says van der Linden, who studies disinformation campaigns. “As soon as we introduce a contrarian perspective, people lose all sense of the weight of the evidence” that supports the consensus.

For years, tobacco companies paid for research that sowed doubt about the overwhelming consensus by independent scientists that cigarettes cause cancer. van der Linden has researched the practice of climate change deniers to stir doubts about the consensus on that issue: They create reports that say some scientists disagree. Many times, the denier scientists have no expertise in climate science — but lay people don’t know that.

The art of science gets turned against science. To researchers like Parikh at the AAAS, “the power of science” lies in continuously challenging what scientists think they know: “We have hypotheses, we test them, and when the data show that those hypotheses aren’t right, we change them.”

To the public, all that adjusting and contradicting of findings raises suspicions of incompetence or worse. “In our polarized world, changing your mind about something based on data is evidence of cover-up, conflict, or corruption,” Parikh says.

Not long ago, this iterative process ran largely out of the public eye.

“For a long time, it was scientists talking with each other and debating these things at conferences and in scientific journals,” says Holly Fernandez Lynch, JD, MBe, the John Russell Dickson, MD, presidential assistant professor of medical ethics in the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Now the public witnesses many of these discussions, thanks to pre-publication access to scientific research before it is fully vetted, the fast spread of research findings (including contradictions of previous findings) through the Internet and social media, and online discussions dissecting (or even ripping apart) research.

“Science is becoming more and more accessible, which is a good thing in one regard,” Fernandez Lynch says. “But that has put on public display this process of debate and iterative approaches to figuring out what is true. That has been a game-changer.”

Groups profit from disinformation. Sure, some disinformation comes from conspiracy-obsessed tweeters with too much free time. But those people get lots of material from well-funded groups with practical objectives: make money, win elections, or advance causes.

“There are actors in this plot who have motives other than being angry,” says Woodcock at the FDA. “There are people who are interjecting themselves into this dialogue in order to accomplish other objectives.”

Companies have attacked government advice about COVID-19 protections and treatments in order to sell alternative, unproven products. For example, some providers continued selling the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine as a protection against COVID-19 even after a study touting its benefits against the disease was retracted.

In other cases, companies use misinformation strategies to protect their profits. Joffe at the Perelman School of Medicine points to oil companies that produced studies casting doubt about the impact of their product on climate change.

“There has been a concerted effort from some quarters to undermine trust in science for private purposes,” Joffe says.

Sometimes those purposes include advancing social agendas. A report by the Center for Countering Digital Hate, based in the United Kingdom, found that 12 anti-vaxxers “are responsible for almost two-thirds of anti-vaccine content circulating on social media platforms.”

Amid the COVID-19 vaccination backlash, anti-vaccine organizations enjoyed an increase in contributions.

*

This all means that doctors, health professionals, and researchers need to better understand the nature of the credibility challenge so they can craft effective countermeasures. Those measures range from physicians strategically responding to disinformation on social media, to institutions working with trusted community leaders to educate the public, to government agencies thwarting information warfare.

Because, as Jacquelyn Mason, director of programs at the nonprofit Media Democracy Fund, told the conference on Disinformation and the Erosion of Democracy about disinformation campaigns: “This isn’t just for fun.”